Epigraphic Collection

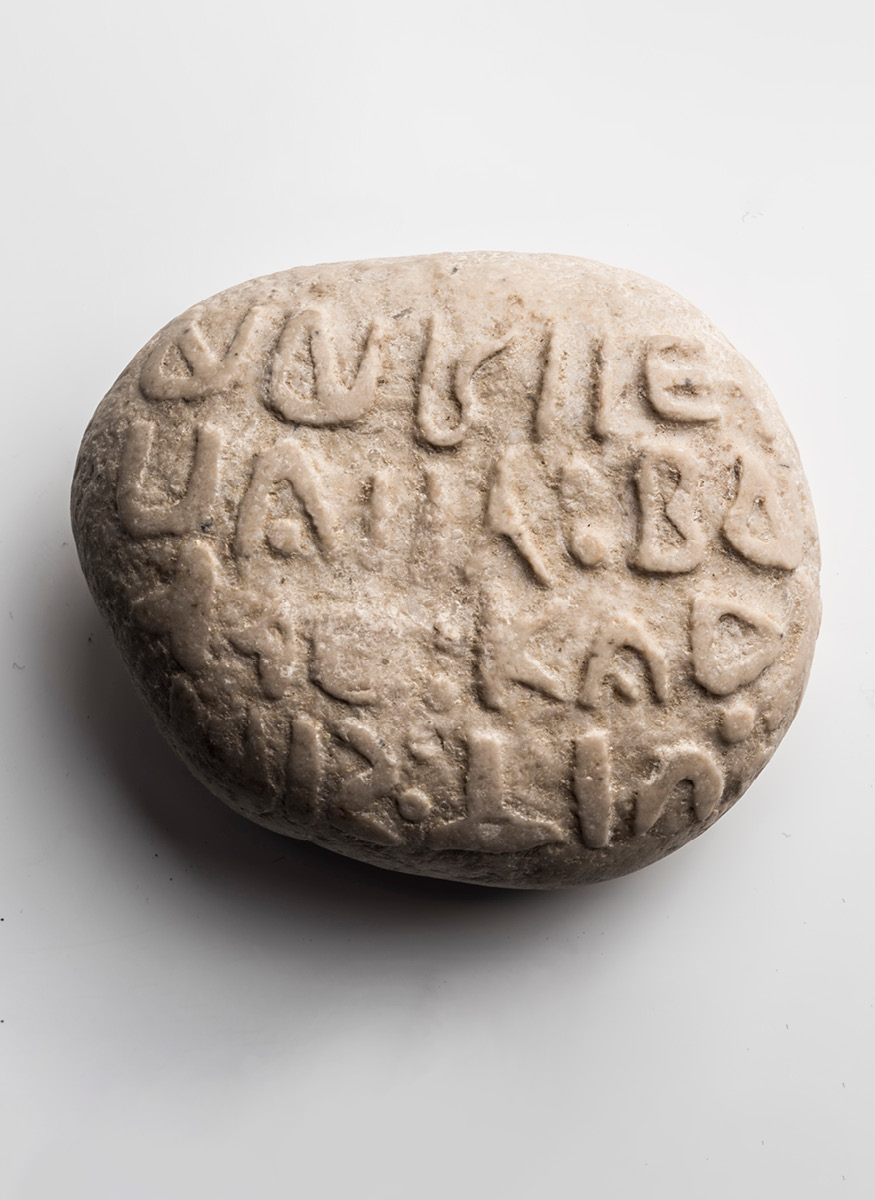

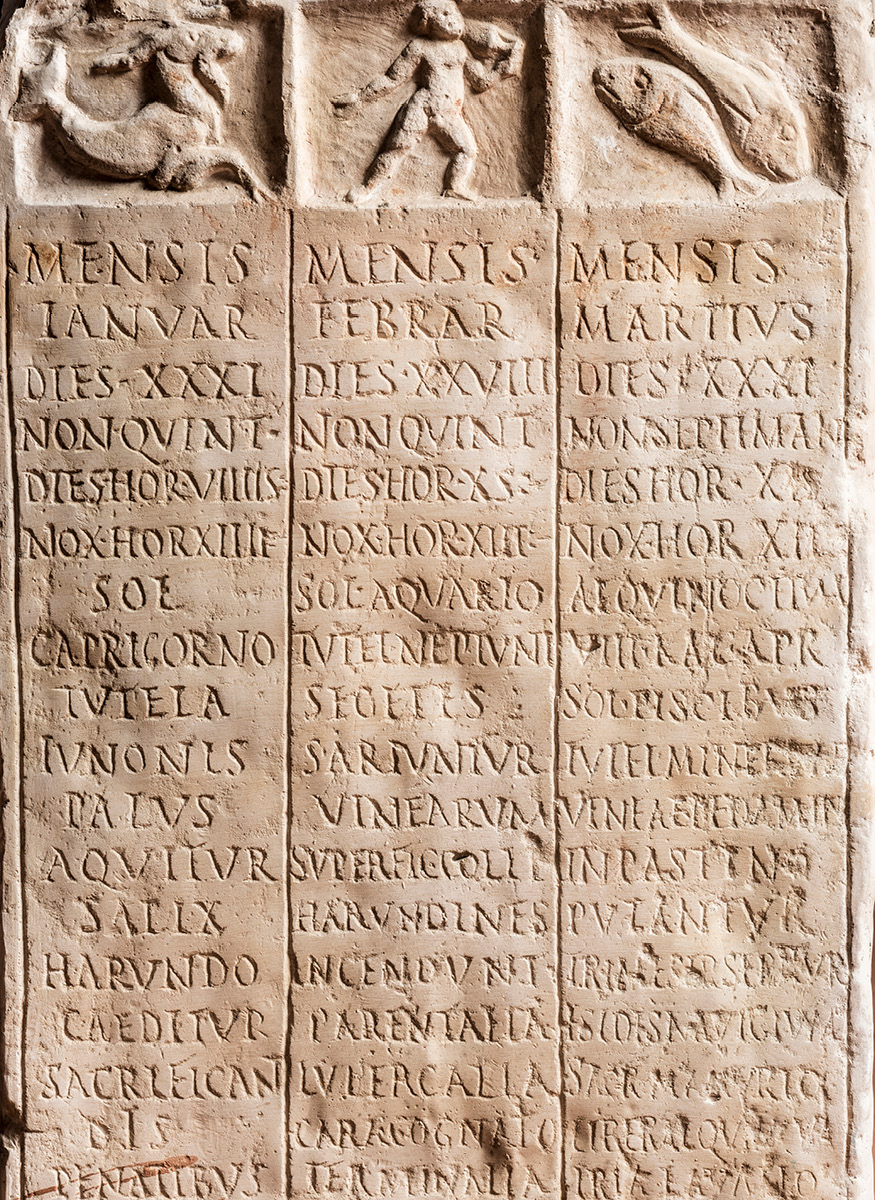

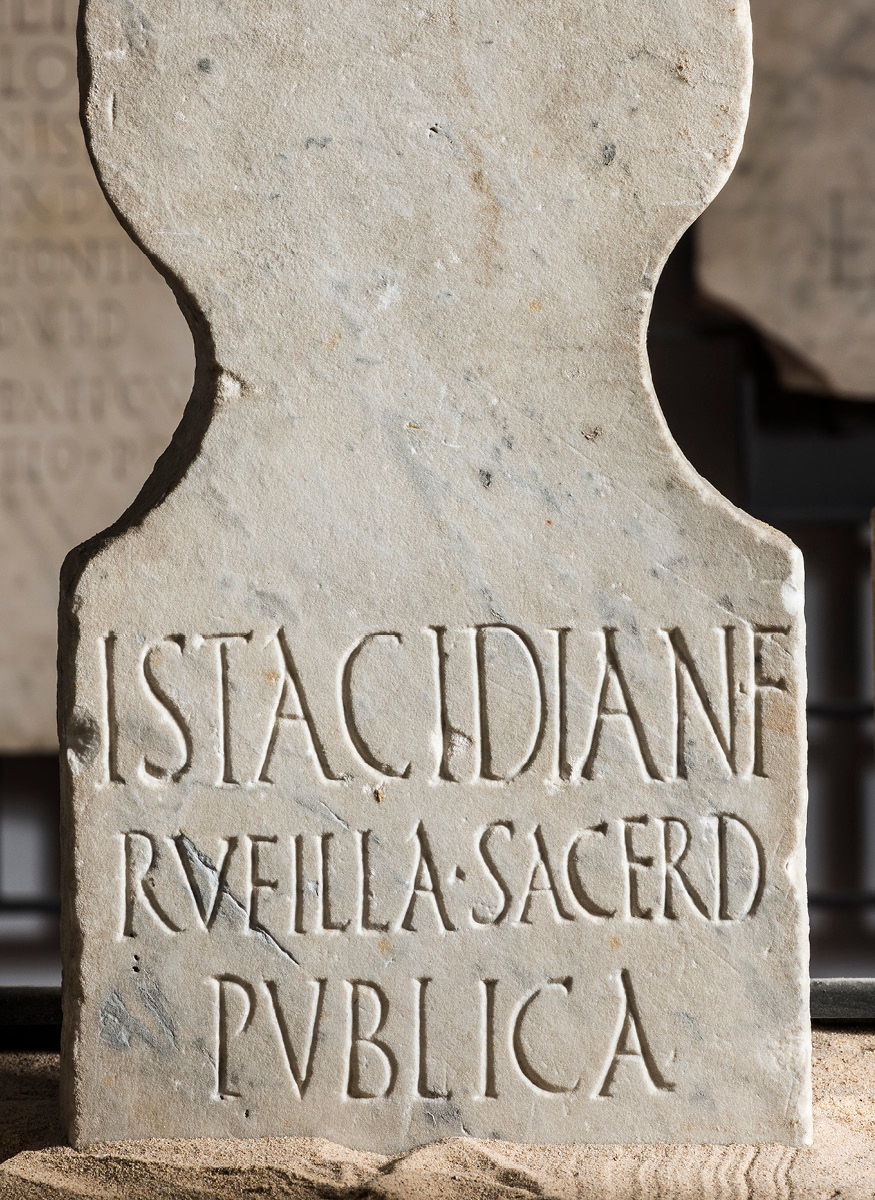

The vast epigraphic heritage of the museum was built up from the 18th century onwards, through both acquisitions on the antiquarian market and discoveries. It offers a snapshot of the main languages used in Central and Southern Italy in a span of time which goes from the 6th century BC to the 2nd century AD. The majority of about two thousand documents is in Latin, plus two hundreds Greek inscriptions and about one hundred in the Italic languages.

The core of the collection is represented by the materials belonging to the Farnese collection, started by Pope Paul III in the mid-16th century and boasting about two hundreds inscriptions from Rome and the Lazio region, which were displayed in the family’s manors either for their documental value or as the evidence of an ideal past. Other collections were purchased by the museum in the mid-19th century: Stefano Borgia’s collection, with its 260 inscriptions from different areas of Umbria and Lazio, was integrated in the museum heritage in 1817; the collection of Francesco Daniele, a man of learning, very fond of numismatic and epigraphic evidence from Campania, entered museum’s possessions in 1812; Carlo Maria Rosini, bishop of Pozzuoli and antiquarian, sold his Phlaegrean inscriptions to the museum in 1856. A quite significant contribution came from the regional area, thanks to the discoveries made by chance, as well as to the excavations promoted in Campania and the whole Southern Italian territories, without any interruption, by the Bourbon kings, till the most recent activities, carried out by Superintendences for protection purposes.

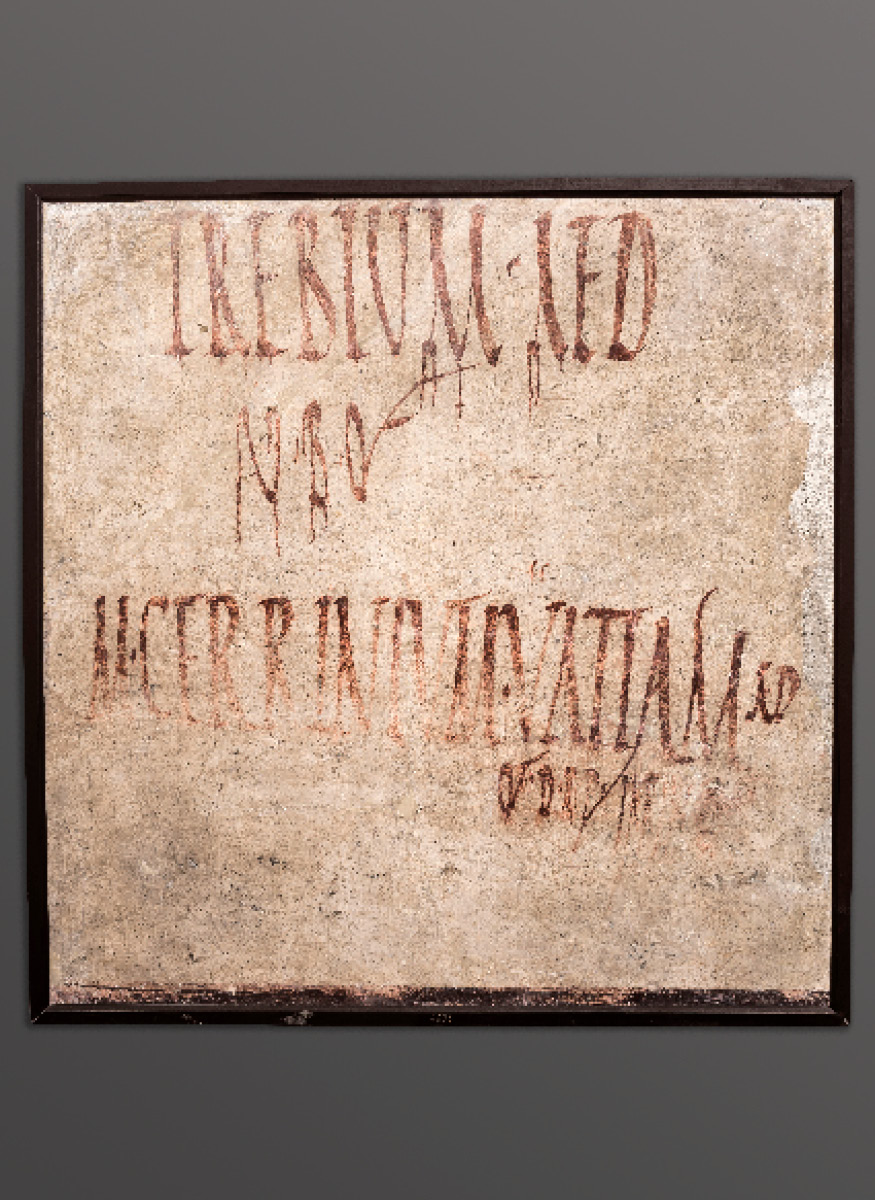

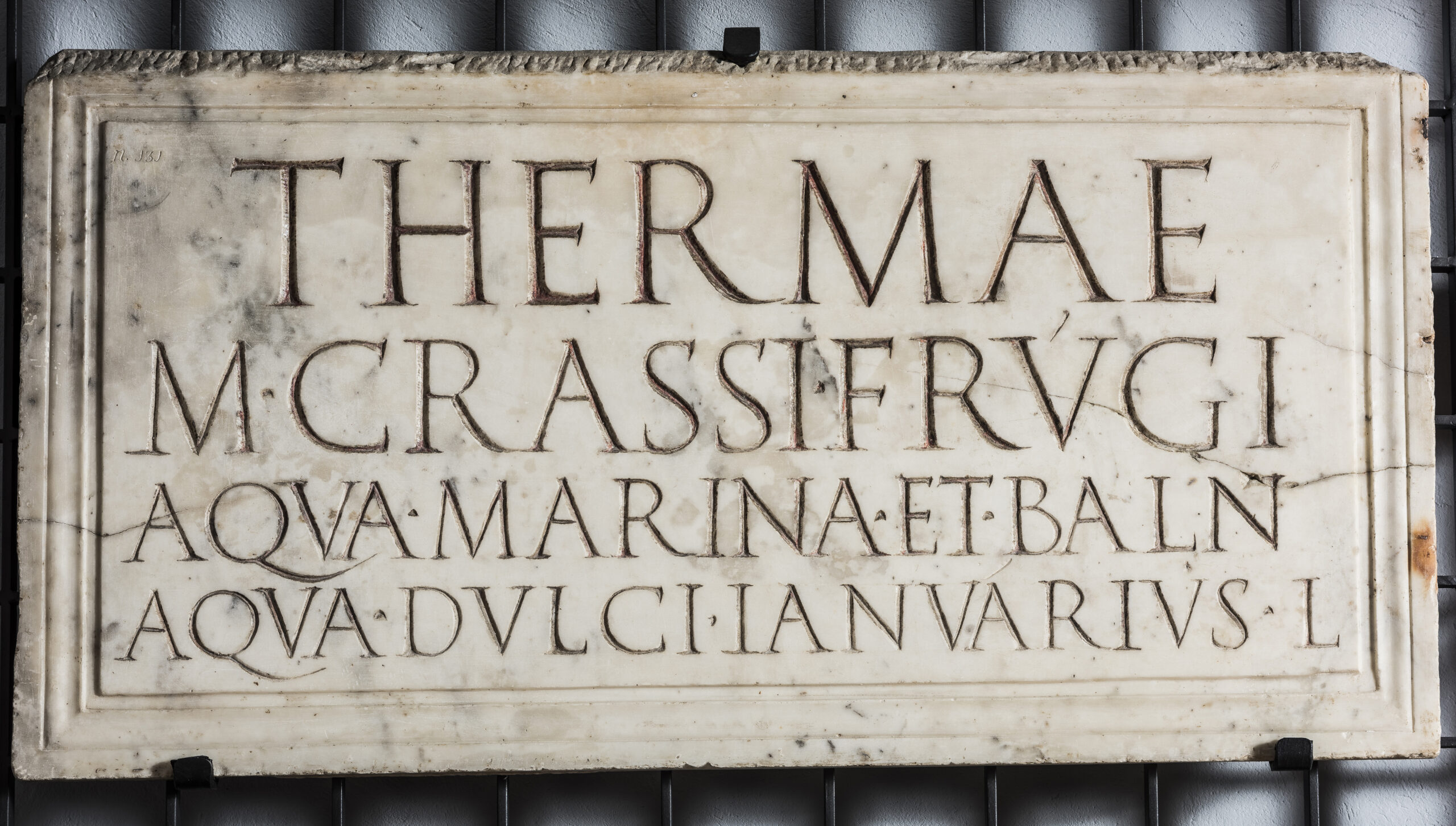

The visit to the collection is organized according to a topographical criterion, focusing on single towns and on exchanges among different language groups. It starts with Magna Graecia colonies, which became, from the 8th century BC, a strategic area for the spreading of the Greek alphabet in the West; a special attention is paid to Neapolis, characterized by a constant use of the Greek language in official documents until the 3rd century AD. The visit continues with evidence of the Oscan language in towns of Campania, such as Capua, Nola Pompeii and Cumae, documenting cults, as well as religious and political institutions. A special place is occupied by the fragment of the Tabula Osca Bantina, the most extensive document in the Oscan language, together with the cast of the Cippo Abellano, associated with other inscriptions from the Irpinian area and the evidence concerning the Samnitic sanctuary of Pietrabbondante. The largest part of the collection is dedicated to the process of integration in the Roman world and to towns like Pompeii, Herculaneum and Pozzuoli, whose public life is known through the names of magistrates, construction works proceedings, cults and activities rules, like bricks or wine-production. The collection also boasts some examples of popular spontaneous writing, such as graffiti or writings on the wall along the streets, which appeared during political competitions and gladiatorial combats.